(Note to readers: Jewish Baseball News invited author and JBN contributor Ron Kaplan to write about his new book on Hank Greenberg and how it came together.)

By Ron Kaplan, contributor

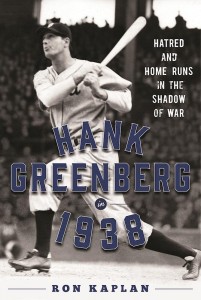

When I first began work on my new book, Hank Greenberg in 1938: Hatred and Home Runs in the Shadow of War, it was going to be a fairly straightforward look at his assault on one of the biggest records in sports, sprinkled with a bit of pop culture.

Just 11 years earlier, Babe Ruth – who had “saved” baseball in the wake of the 1919 “Black Sox” scandal with his oversized personality and heretofore unheard-of power hitting – smashed 60 home runs, more than any other team in the American League. Jimmy Foxx, aka The Beast, came close with 58 blasts in 1932 as a member of the Philadelphia Athletics, but that was it. Then Hank Greenberg comes along to open up discussion about a possible new home run king.

Things started off slowly for the Tigers in 1938 after they had finished the previous four seasons first or second in the junior circuit. Greenberg, too, wasn’t breaking down any doors early on; at one point that June, he went 12 straight games without a home run. Although he had 22 by the end of the month, that still didn’t raise too many eyebrows.

Over the last three months of the season, however, Greenberg distributed 36 round-trippers: 15 in July, slumping a bit with only nine in August, and making a run of it with 12 in September and October (but none over his final five contests). And with the Tigers pretty much out of the pennant picture all season, fans embraced his individual performance. The more times Greenberg crossed the plate on his own, the wider the notoriety spread. Newspapers ran charts and illustrations showing where he stood in relationship to Ruth at any given point of the campaign.

In the end, Greenberg just ran out of time, literally and figuratively. Early season rainouts had to be rescheduled as late season doubleheaders. Since none of the stadiums in the league had lights yet, several of those nightcaps were halted early as darkness descended, depriving Hammerin’ Hank of precious at-bats, and as we know, he just couldn’t catch the Babe, finishing the season with 58 homers. The final game, a meaningless 10-8 win over the Indians in Cleveland on a cold afternoon in October, was called after seven innings. The home plate umpire was apologetic when he informed Greenberg, “I’m sorry, Hank. But this is as far as I can go.” The ballplayer responded without anger. “That’s all right. This is as far as I can go, too.”

While it was fascinating to scour digitized versions of old newspapers – they just don’t write ‘em like that any more – the narrow focus of the topic of this book gradually expanded from the sports pages to the front pages. As the title plainly states, this isn’t an overall biography of Greenberg. There’s no competing with John Rosengren’s excellent Hank Greenberg: The Hero of Heroes or Greenberg’s own memoir, reverently “rewritten” with the help of Pulitzer Prize-winning Ira Berkow. Not to mention Aviva Kemper’s award-winning documentary, The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg. I was tasked by my publisher to specifically address what else was going on in the United States and the world in that seminal year of 1938. The U.S. was still in the grasp of the Great Depression and Hitler and his cronies were flexing their fascist muscles. Baseball was a welcome distraction.

There’s a line from the classic film It’s a Wonderful Life in which a character defends George Bailey’s not serving in World War II (he was actually unfit for service because of deafness in one ear). “Not every heel was in Germany and Japan,” he says. This is where some unfortunate parallels between Greenberg’s era and modern-day circumstances come into focus, issues that had not yet been a consideration as I worked on the manuscript for an October deadline.

In 1938, the United States (as well as other countries) was extremely reluctant to accept Jewish refugees trying to flee Nazi oppression. Compare that with the current administration’s policy on Syrian refugees.

In 1938, the United States did not want to enter into another international fracas. Isolationism was a watchword and its slogan was “America First.” Sound familiar?

Finally, Greenberg worked in a city that “boasted” two of the most notorious anti-Semites of all time: Henry Ford and radio fire-and-brimstone preacher Father Charles Coughlin. After the 1919 World Series scandal, Ford’s newspaper, the Dearborn Independent, wrote that the problem with America’s national pastime could be summed up in three words: “Too much Jew.” Coughlin had referred to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s massive infrastructure programs as “the Jew Deal.” Since the current president took office in 2017, there has been an uptick in hate crimes.

Pundits have suggested that anti-Semitism might have been the reason Greenberg didn’t break Ruth’s record, that there was a conspiracy to prevent a Jewish man from achieving such glory, just as there was another “gentleman’s agreement” to keep black players out of organized baseball. To his credit, Greenberg never used that as an excuse. He just chalked it up to fatigue and wear-and-tear: he only missed two innings over the course of the year, both of those coming in the same game.

According to the song title, “Everything Old Is New Again.” Unfortunately, that seems to go for the bad as well as the good.

Ron Kaplan (@RonKaplanNJ) hosts Kaplan’s Korner, a blog about Jews and sports. He is the author of three books, including The Jewish Olympics: The History of the Maccabiah Games and the forthcoming Hank Greenberg in 1938: Hatred and Home Runs in the Shadow of War.

# # #

Get your Jewish Baseball News updates via e-mail